|

An article at Quartz at Work examines Maslow and the pyramid that he never built but that is usually attributed to him. The piece cites some insights I shared previously in a "Talking About Organizations" podcast episode as well as the work of other great academic colleagues published in the Academy of Management Learning & Education Journal.

May 2019 Together with some colleagues from Alberta, we explored the main modes through which qualitative data is presented in organization and management journals in an attempt to stress the importance of avoiding a one-size-fits-all approach and embrace creativity in the way we organize and showcase our data. The paper has been recently published as part of a Research in the Sociology of Organization on "The Production of Managerial Knowledge and Organization Theory: New Approaches to Writing, Producing, and Consuming Theory." Check it out!

https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/S0733-558X20190000059011 Sharing your work and receiving feedback is always great. But it has a unique flavor when you have the chance to dialogue with colleagues from your institution. I presented at emlyon a working paper on how bureaucracy shapes the organization of knoweldge work and got constructive comments on how to push the work further. The occasion was celebrated with an "I heart bureaucracy" cake made by me!

March 2019Sometimes it seems that all factors come together to create a great academic event - dazzling nature, good company, great food, inspiring ideas, sharp debates, etc. The emlyon workshop in Chamonix had all this and more. In it, PhD and postdocs discussed each other's papers with also the benefit of comments from senior academics. It was super enriching for my work and overall just very fun.

March 2019 In the end of march, I had the wonderful opportunity to present my academic work on Bureaucracy and Knowledge Work at Copenhagen Business School (CBS) following an invitation from Professor Paul du Gay from the Department of Organization (IOA). The event brought together members of the VELUX and POVI groups at CBS and also included a presentation by Bernardo Zacka on his work on street-level bureaucracy. My talk examined how bureaucratic structures shape what counts as expertise and knowledge work dynamics in organizations. The comments were superb and it was energizing to meet fellow scholars interested in formal organization in my field! Full details here: https://cbs.nemtilmeld.dk/44/it-5CPW8RM7,19867,30726/

February 2019 I am thrilled to learn that I am a finalist for the EGOS Max Boisot Award for my paper on "Back to the Future: Bureaucracy as an infrastructure for Collaborative Knowledge Work" together with other great scholars. I am particularly delighted because EGOS has been central in my academic career and the first papers I read about knowledge work were the ones published in its flagship journal. Special thank for all my wonderful colleagues who continuously help me during my journey! While the paper/nomination is individual, scholarship is always a team sport. See you in Edinburgh this summer at the awards ceremony when the winner will be announced.

January 2019 Dear Colleagues, This is a friendly reminder that we welcome submissions to our EGOS 2019 sub-theme on Formal Organization Today. Our goal is to bring together people interested in formal organization broadly understood. That is, empirical or theoretical papers exploring aspects of formal organization (e.g., organization structure, formalization, hierarchy, bureaucracy, etc), as well as organizational dynamics, theorized in relation to formal organization (e.g., coordination, control, socialization, learning, innovation, etc), including the link between 'informal' and 'formal' organizing. We are open to studies in any setting or industry (corporations, public sector, cooperatives, activist groups, etc). We promise a constructive and pleasant session — with homemade baked goods to boot! European Group for Organizational Studies (EGOS) 35th EGOS Colloquium, Edinburgh (UK), 4-6 July 2019 Formal Organization Today: Reconnecting with the Classics (subtheme 45) Convenors: Pedro Monteiro, emlyon business school, France, monteiro.research@gmail.com Paul du Gay, Royal Holloway, University of London, UK, Paul.duGay@rhul.ac.uk Signe Vikkelsø, Copenhagen Business School, Denmark, ssv.ioa@cbs.dk Call for Papers

Concepts and discussions on classic organizational authors currently seem to be relegated to the pages of manuals and history books (Adler, 2009). In particular, formal organizational dynamics (e.g., bureaucracy, staff-line relations, work formalization) occupy a secondary role in the current literature (du Gay & Vikkelsø, 2016). Most contemporary studies explore societal matters, work interactions, and new organizational forms, while leaving formal organizational aspects — which were once core in our discipline — in the background. In part, this state of affairs is due to the development of the field which has been enriched by new themes and approaches (Lounsbury & Beckman, 2015). Yet, we also suffer from a ‘novelty bias’ and at times do not pause to explore how new ideas fit within the canons of our discipline (Barley, 2015). The goal of this sub-theme is to stimulate an appraisal for our fundamental object of inquiry: formal organizations. In light of the theme of EGOS 2019, we believe that we can “enlighten the future” by (re)connecting with the classics (Blau & Scott, 1962; March & Simon, 1958). For example, bureaucracy is still central in the modern workplace (Adler 2012; Walton, 2005). Yet we know little about how technical and social innovations are re-shaping it, and its relationship with emerging organizational forms (Bernstein, Bunch, & Canner, 2016; Turco, 2016). Similarly, although we might be living in an age of experts, there is still much to be learned about the interplay between formal organizational mechanisms, informal/emergent dynamics and professional/knowledge work (Bechky & Chung, 2017; Brivot, 2011; Langfred & Rockmann, 2016; McEvily, Soda, & Tortoriello, 2014). Also, we know that some companies today only with a few dozen workers are able to occupy an economic position which was once reserved to corporate giants (Davis, 2016). Yet this does not mean that vertical firms — and the challenges associated with them — have disappeared. Finally, despite many changes in society, coordination and control (classic organizational themes) remain a key concern for both online and offline work (Dahlander & O'Mahony, 2014; Huising, 2014). This subtheme thus seeks to stimulate scholars to explore formal organizations both as an empirical phenomenon, as well as a source of theoretical problematics. High-quality, novel contributions in both early and later stages of development are warmly invited. In particular, papers may address issues related (but not limited) to the following topics:

Further Details EGOS is organized as a collection of workshops in which participants spend all three days of the conference in the sub-theme in which their paper has been accepted. This allows for an immersive experience with ample space for conversations. For further information about the conference, please check: https://www.egosnet.org/2019_edinburgh/CfP. For information on sub-theme 45, please check: https://bit.ly/2xdstK5. The schedule for submissions is as follows: Deadline Short papers (3,000 words) to be submitted via EGOS site: January 14, 2019 Notification of acceptance, rerouting, or rejection of papers: End of February, 2019 Full papers to be uploaded to the EGOS website: Mid-June, 2019 For further information, please contact Pedro Monteiro at monteiro.research@gmail.com or monteiro@em-lyon.com December 2018 The Ethnography Atelier Podcast is an initiative by Ruthanne Huising and I with the support of emlyon business school. Our goal is discussing research methods with accomplished qualitative researchers. We talk to guests about their experiences of conducting research in and around organizations, the challenges they faced and the understandings they gained. The podcast is part of the ethnography atelier work to promotes ethnographic and other qualitative research. Listen to the Ethnography Atelier Podcast:

https://itunes.apple.com/gb/podcast/ethnography-atelier-podcast/id1444653741?mt=2 https://www.ethnographyatelier.org/podcast November 2018 As the winner of the Louis Pondy Award, I had the privilege of interviewing Alan Meyer, the OMT Distinguished Scholar of 2018. This was a wonderful opportunity to pick the brain of a great organization researcher. We talked about the organization and management theory field, the value of community in scholarship, internationalization, and a whole bunch of things. The interview transcript is available below and the full audio is available via this link: https://www.dropbox.com/s/0w80u6ntuxx6c0g/Alan%20Meyer%20OMT%20Interview.mp3?dl=0&fbclid=IwAR1vX7-1IajhMaga7WnuzkGnwqOEozyCGAaKTOfjHA1BHlBAW8IElZwYZaY OMT Is the Place to Be: An Interview with Alan Meyer Pedro: Congratulations on your award. Let’s start at the beginning of your career. What motivated you to go to grad school in California and eventually become an organizational theorist?

Alan: I’ve always had a thing about universities, I love them! I had a great time studying economics at the University of Washington as an undergrad. My MBA wasn’t quite so much fun, but it was better than being drafted to Vietnam. From there I got a job teaching at Alabama State University, one of the historically black universities, and that was where I figured out that I had a lot of fun in the classroom. So that pushed me to apply for PhD programs. I mean, what could be better than being at Berkeley in the seventies. As far as why organization theory, I think that was really based on random encounters with some smart and sort of kind-hearted mentors. Lee Beach, a decision theory psychologist at the University of Washington, a guy named Charles Summer, who was the President of the Academy of Management long ago. And then Ray Miles and George Strauss at Berkeley, and Bill Starbuck. I don’t think organizations were attractive to me until I was well into my studies — I was on an exploratory mindset. Pedro: You explored manofy different themes and approaches in your career. Is there an invisible red thread connecting them? Do you think that having a “coherent” research program is even desirable? Alan: That’s a great question. If I’m candid, I was driven mostly by curiosity. In retrospect, it’s easy to find some ‘red threads.’ Starting with my dissertation, I was especially interested in organizations' reactions to upheavals that were going on in their environments. You know, technological discontinuities, the doctors’ strike, regulatory changes, those sorts of jolts. I figured out early on that although it messed up your research designs more often than not, very interesting things happen during those episodes when an organization gets knocked away from equilibrium. Along with that, I’d gotten increasingly interested in emergence and self-organizing and things like auto-catalysis and so forth. You know, only about maybe 90% of organization science is the science of organizing either at equilibrium, orreally, really close to it. But that other 10% is pretty interesting! Pedro: In your talk at AOM 2018 (link here), you raised a number of interesting points. What do you hope OMT members took away from your presentation in Chicago? Alan: In this talk, I represented and interpreted my career in terms of a social network that was built out of an Invisible College consisting of a set of 174 relationships that I’d formed with 112 different colleagues. About 90% of the people and the connections in my network have been drawn from the OMT division. And that was a big surprise to me. I also realized that all of my research, at least all of the one I'm proud of, was leveraged out of that social network. So, one thing that I hope people took away is a different, and maybe a deeper appreciation of why OMT matters and what it can do for them. I think we have something powerful going on here. So, what makes OMT special? First, OMT sits at a sweet spot. It’s serving a function that no other division in the academy can do. It closes that structural hole between the micro hub with OB at its center and the macro hub which has strategy as its hub. We’re sitting right at the crossroads. A second thing that I discovered is that OMT is associated with greater longevity: on average, its members have longer tenure than any of the other divisions. So, people stay. And I think one of the reasons they remain is because OMT harbors this colony of cooperators, of people whoreally are kind-hearted, who have high standards and integrity. Pedro: I wanted to dig a bit deeper into the idea of being at the intersection. What do you think it means in practical terms? Are we the bastion of a specific kind of theorizing or questions? Alan: I think we are sitting at a meso-level. You know, as organizations sort of begin to dematerialize and disaggregate into global networks and so forth, we’re sort of uniquely positioned to, when necessary, go down a level of analysis and see the groups that are being plugged into and out of these networks. Or to pop up to the next higher level of analysis and look at those changes in the structure of the fields in which organizations are sitting. Organizations may be morphing from rigid, formal, bureaucratic types as per the classics, into what Jerry Davis calls a network of contracts. But whether you believe that or not, you're still sitting at a pretty sweet spot to be able to go where you need to go, to understand organizations and management. Pedro: I am curious about your work concerning the African Academy of Management and indigenous scholarship — both timely in light of current talks about internationalization in OMT. What was the inspiration to engage in that? Alan: Jim Walsh was the one who led the initiative to take the Academy to Africa and convened groups of about twenty-some young African scholars from across the continent, and put them in a boot camp-style situation similar to a typical OMT consortium. It was a very highly interactive and immersive experience. One remarkable thing to me was to discover that it was felt as a quasi-spiritual event by participants. I mean, I almost felt sort of cheap, rolling out little snippets of PhD 101, stuff that I’ve taught and used in workshops and classes over the years, as it was received there as a ‘sacred’ gift that produced tremendous insights. The participants were so ready! Just a small input had immediate, remarkable consequences. Yet that initiative has run its course, and it turned out to be challenging to find sponsorships for pan-Africa events. It probably would have been a smarter move if we wanted to sustain the program to focus on one nation at a time. Pedro: This makes me think of the Invisible College. In academia, our collaborations are usually unscripted, and we work with people we are familiar with … but this can exclude minorities and people from non-traditional backgrounds. So, do you think there can be a dark side to it? Alan: In short, yes, there is a dark side, I think. Although I don’t have anything to say that is close to a solution, but I honestly do feel that OMT harbors a lot of people whose values are very inclusionary. It is a place of social inclusion in my opinion, more so than some of the more rigidly pragmatic fields, or those based on skillsets and tools or do not see the rationale for being particularly sensitive to the kinds of issues that you're raising there. In short, I would say: stay in OMT, and you’re less likely to be excluded! There has been a lot of work by Emily Block and many others, including Marc-David Seidel trying to figure out how to make everyone feel at home and welcomed in OMT. The other positive initiative that comes to mind is the one Andy Van de Ven structured about indigenous engaged scholarship. But there’s no question that I had a privileged point of access to a pretty sweet set of colleagues, that somebody in Africa or Brazil, you know, or Peoria, Indiana, doesn’t necessarily have. Pedro: Thank you for this reflection, and I agree that on/off-program initiatives may bring people together in a unique way and create space for ‘random' encounters beyond one's network. Alan: I guess the other bright spot is that as people go through their academic careers and arrive at a more senior position, they take on a service orientation to the academy as an organization. I guess the action implication here is to, first of all, expect that and nurture it among colleagues, that transition from being more output-focused and research-focused to being more service oriented and a little bit more reflective. Pedro: You probably accumulated a lot of lessons in your career. What would you tell your younger self that might be relevant to junior OMTers? Alan: What advice would I give myself? There are things that I did not figure out until later, that would have been great to know. The first thing, if I could put a bug in my ear back when I was 25 or 26, I would say: ‘Hey, you know, congratulations, you have just stepped into the best job on the planet!’ Think about it. We get to design our jobs ourselves; we can study whoever, whatever we like, almost anything or anyone that arouses our curiosity. We also get to pick ourown co-workers, and that’s something that’s not quite so often appreciated. Try to give me an example of a job where you can decide who your closest colleagues are going to be? There are various strategies; mine has been, because I've never been really productive in the volume sense, I haven’t had a lot of time to build a social life and research career, and so I’ve made a practice of working with my friends and getting friendly with the people that I'm collaborating with. And this has been a tremendous work-life integration because our families grew up together and we seek each other out for fun, as well as for academic research. A second piece of advice I would tell myself is to avoid the rooky mistake of believing that research and scholarship are solitary pursuits. What I’ve learned, fortunately relatively quickly, is that scholarship and research are incredibly social. And you know, the whole exercise of deconstructing and reconstructing my network, indeed drove that home for me. A related rooky mistake of seeing scholarship as solitary is thinking that my identity as a scholar is going to take shape in sort of a natural, organic fashion. That it would be some function of my values, my beliefs, the skills that I’ve developed. Once again, totally wrong. At least looking backward at it, I’d think that a young person has the opportunity to carve out an academic identity, and to change it when necessary, when desirable, when you're bored, or when some new intriguing opportunity presents itself, you have that kind of control. A third lesson — that I was lucky to learn early on because of the people I was studying with is building a field research component into every study that you do. I'm not a particularly extroverted person, but being a field researcher gives you the license to go into people’s worlds, to collect data from them by interacting with them on their own turf. You have to understand what they care about to keep them engaged in the conversation, you have to learn their jargon so that you can talk to them, and in the process, it opens windows into just really incredibly fascinating occupational worlds. Another painfully-learned lesson was to be compulsive about craftsmanship. That means things like, do not submit your paper prematurely, use your colleagues as a sounding board. When you've got something written, volunteer to give a talk about it. When it’s written, circulate your draft and persuade people that you do not want them to pull their punches, and then treatand every misinterpretation of what you've written, as evidence that you still haven’t figured out how to communicate it correctly. And I think the last point is, you don’t have to trade off quality for quantity. Believe me. There are many people in our field that do care about quality, they're looking for it, they know it when they see it, they're prepared to reward it. So, your goals can be not to get published, but to get read and get noticed and to make a compelling case for your position. And you know, life’s too short, you need to give yourselves those kinds of intrinsic rewards, as opposed to succumbing to the pressure to slice your data thinly and multiply your publications and so forth. Pedro: We talked about the past and reflected a bit on your path. So, what about the future? What are the trends that you see and what do you think the future holds for OMT? Alan: I think it holds some real disruption. There’s a narrative in the social sciences and in organization theory that’s in pretty heavy rotation. Academic publishing is in shambles. There’s all this p-hacking going on – that was never a problem when I was a kid. There’s the replication crisis in psychology; there’s been this massive surge in article retractions in our field, as well as in medicine. And authors are getting pretty testy; they're complaining about editors that are hijacking their articles and almost becoming complicit co-authors, that reviewers are forcing them to rewrite their hypotheses. Once again, I would invoke OMT as I think of the first layer of protection against being infected by some of those nasty viruses. But I think a good editor is going to increasingly have to be prepared to be disrupted. For me, a good editor is somebody who acts like an author is his or her social and intellectual peer. And that sounds kind of obvious, but it’s not. I'm talking about somebody that writes comments as though he or she was speaking to the author personally. One of my favorite quotes is from H.G. Wells, who said: “no passion in the world is equal to the passion to alter someone else’s draft.” So editors need to learn how to curb their enthusiasm for doing that. But maybe even more important is to realize that academic publishing is, as I said, on the cusp of being disrupted. You know, paper journals are disappearing, authors are self-publishing at websites, like SSRN and Research Gate. We’ve got these alternative reputation systems that are popping up on social media platforms, like Mendeley and LinkedIn. I would not want to own an academic journal. I think they’ve extracted surplus value from the research and publication process at too high a rate for too long, and I’d go short on academic journals right now. It’s going to bereally interesting to watch what happens to promotion in tenure reviews and journals. Because they’veof had sort of a conspiracy to slow down open sciencedoesn’t – you know, it serves both of their interests to maintain the status quo. But times are changing. Pedro: Thank you for this great chat! It was enlightening. I am sure the OMT community will appreciate your insights. Alan: My pleasure. November 2018 Last summer, I had the great honour to receive the Academy of Management's Louis R. Pondy Award for a paper based on my PhD dissertation. I was then interviewed by Georg Reischauer in relation to this achievement for the Organization and Management Theory Division newsletter. The interview is available below. Interview with the winner of the 2018 Louis Pondy Best Dissertation Paper Award The Louis Pondy Best Dissertation Paper Award is awarded to the best paper deriving from a dissertation. In 2018, the winner is Pedro Monteiro (Warwick Business School) with this paper “The Enabling Roles of Bureaucracy in Cross-Expertise Collaboration” Congratulations on being the winner of the Louis Pondy Best Dissertation Paper Award! Can you briefly elaborate on what is your paper is about?

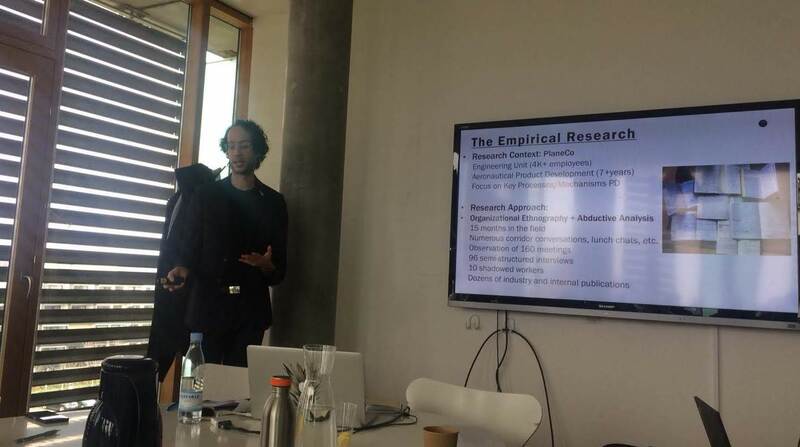

Thank you! It is a great honor to receive this award, and I am very grateful to the OMT community for the recognition. This paper reflects my overall research interest in bureaucracy and formal organizational dynamics. The word “bureaucracy” usually triggers negative ideas, and some of the business press tends to perceive it as obsolete. Yet my research shows that, under certain conditions, it is not only an essential feature of contemporary organizations but also beneficial to work processes such as collaboration. In the paper, I follow a practice approach and use data from a 15-month ethnography of the product development in an aeronautical company to show how bureaucracy supports the interdependent work of multiple specialists. More specifically, I examine how formal organizational elements typical of a bureaucratic structure — such as written records, procedures, and formal roles — facilitate interactions and exchanges across a variety of technical experts, enable them to achieve systemic solutions, and help to address interface issues and conflicts. This contributes to discussions on collaborative work across expertise domains by unpacking the role of bureaucracy in ironing out interdependencies and counter-balancing political barriers and collaboration overload. Moreover, my study also has implications for the broader organizational literature by pointing out some conditions that underpin the enabling values of bureaucracy. The paper explores the role of bureaucracy in cross-expertise collaboration. What motivated to engage with the classic yet highly important organizational phenomena of bureaucracy? I think that engaging with ‘classic’ authors and ideas is a hallmark of good scholarship. Thus, in my work, I continually strive to engage with foundational discussions. I am especially interested in formal organization dynamics and its problematics such as organization structure, coordination, authority relations, formalization, and so on. This is in part because I believe that investigating these issues — be it in corporations, social enterprises, events, online, etc. — is what differentiates us, as organization and management scholars. These two concerns merge into a focus on bureaucracy. Bureaucracy is still a fact of life in and around organizations. Yet most people, including academics, sometimes complain about it too quickly, without considering its complexity. My goal is to go beyond this bias and examine its nature and implications for contemporary organizations. I believe that this can, in turn, lead to significant theoretical and practical contributions as bureaucracy is linked to many social and corporate challenges such as teamwork, innovation, gender equality, and so on. You conducted a fascinating 15-month ethnography. Can you share your experiences of zooming in and out of the field? My fieldwork was divided into two periods. The first one had a more exploratory character during which my aim was to get acquainted with the structure, history, and ethos of the organization. I then took a break from the field during which, among other things, I analyzed and reflected on my initial findings. This was when I decided to focus on bureaucracy and returned to the company with a more focused approach. For me, ethnography does not only entail ‘being somewhere’ but more generally immersing oneself within a specific universe and phenomena. So, throughout all this period, I tried to learn as much as I could about the aeronautical world: I visited engineering schools, attended fairs, and read books about the industry. I also actively searched for information about the company online and offline. For example, some of my favorite stories, including a vignette in my thesis, emerged from conversations with taxi drivers working in the company headquarters area. When studying a large corporation, it is fascinating how much you can gather about it from a variety of sources! Your paper provides rich insights on the role of bureaucracy in professional setting. How did professionals respond to your findings? I am still waiting to discover what the reaction will be. At the end of my fieldwork, I returned to the company to share a feedback report and deliver a couple of presentations. I tried to make the report a practical one, echoing concerns I knew were present in the organization. It mostly documented some integration mechanisms and explored possible ways to sustain further collaboration in the product development based on the literature and previous research from the IKON research group in the Warwick Business School. While the report was positively received, it leverages only part of my findings. So, once I manage to get some academic publications out, I hope to distill further ‘practical’ insights from my research. I am curious myself to learn what professionals will say about my ideas related to bureaucracy. From conversations, my impression is that people are curious and a bit puzzled about the idea of designing bureaucracy to help collaboration. Would you like to share any challenges you faced during the research and writing process? If so, how did you overcome them? I mentioned above that fieldwork was divided into two parts. Although this arrangement worked well, it emerged partially due to access difficulties. Because it was restricted at first, my solution was to focus on ‘breadth’ until I could explore the company freely and thus dive into specific situations and processes. My strategy was one that is well known to ethnographers: remain persistent and make the most of what you have. Trying to grasp bureaucracy empirically also presented challenges. This was in part because my goal was to use the Weberian ideal-type as a guide for fieldwork, not a fixed ‘measure’ as done by some previous research. Besides finding inspiration in earlier research, such as the work of Alvin Gouldner, I was also influenced by the artwork of Carl Hammoud. His images foreground aspects of organizational reality which are not always obvious and helped me ‘see the bureaucracy’ behind the many events and interactions I was looking at in the field. Finally, writing everything up was not always straightforward. Yet I was lucky to have access to some great resources. I attended a workshop by Karin Golden-Biddle early in my PhD which was super useful, her book on writing is also very didactic. I also found the interviews collected by the Project Scrib quite helpful as they show that we all struggle with putting ideas on paper. And finally, I was lucky enough to have many colleagues who helped me clarify my insights. In particular, I benefited from wonderful conversations with the members of the Talking About Organizations Podcast which I am one of the co-founders. Again, congratulations for winning the Louis Pondy Best Dissertation Paper Award! Is there anything else you would like to share with the OMT community? I would like to thank all those who supported my work. Scholarship for me is a team sport: one’s work depends on peers who help to bring it to life. Also, special thanks to the company where I conducted my fieldwork and the immense generosity of all those who I met while there. A big thank you to my supervisors from Warwick Business School, Davide Nicolini, and Hari Tsoukas, as well as all those who helped me to clarify my findings and write up the thesis and related paper. I also would like to share a general reflection with the OMT community. I am only a novice, but sometimes I feel that we have lost touch with some of the core concerns of our field. Namely, a focus on formal organization issues and a meso organizational dimension. While I heartily appreciate the diversity under the OMT umbrella, I feel that many conversations could be enriched by establishing connections with meso-level dynamics and classic literature. Finally, do you have any advice for colleagues who aspire to win the award in the future? I am probably biased … but I take the award as a signal of an enduring appreciation for research that explores classic organizational themes and addresses empirical puzzles, even though it might sometimes seem that theoretical problems and new topics are sovereign. Yet, more than a piece of advice, what I have is an invitation: engage with the classics, explore puzzles in the world, and continually ask yourself what is distinctively ‘organizational’ about your research. And if any of these excite you, do get in touch! It is always a pleasure to hear from like-minded colleagues. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed